Introduction

Biodiversity change and loss is a critical global environmental concern, which can ultimately impact human wellbeing by reducing ecosystems’ capacity to deliver ecosystem services. Biodiversity change is mainly driven by human-induced factors such as population growth and land use changes linked to economic development, which have directly and indirectly transformed Earth’s landscapes.

In our recent paper, published in Sustainability, we investigate how biodiversity responds in the long run to two variables – the Human Footprint Index (HFI) and the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The HFI directly measures human impact on ecosystems by combining various pressures (including built environments, population density, roads, railways, and others) into a single metric. Economic growth, typically quantified by GDP, is an indirect driver that shapes the trends in these direct pressures. GDP is often associated with improvements in human wellbeing, but it overlooks social and environmental factors that are fundamental to wellbeing. While ecosystems provide essential inputs for economic growth, the demands placed on natural resources point to a possible conflict with biodiversity preservation.

Methodology

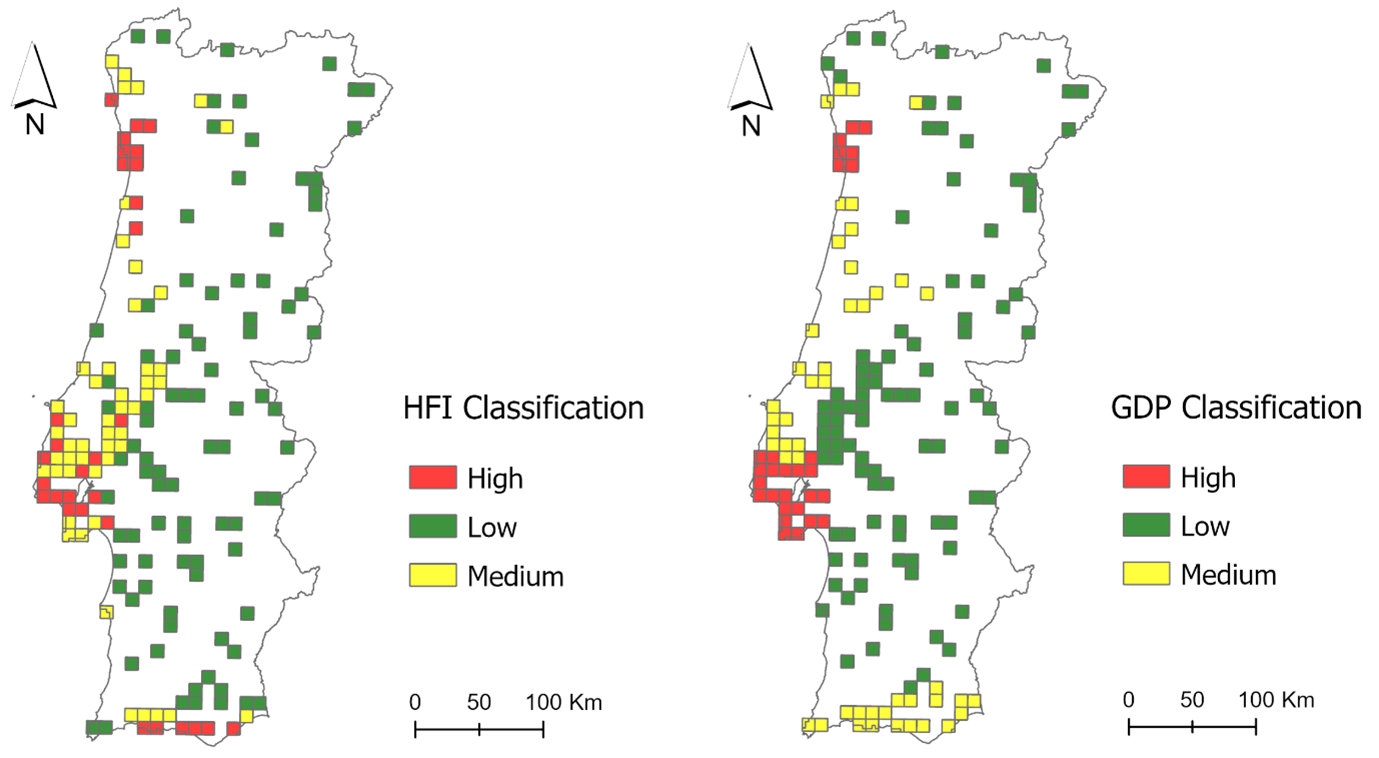

Our study employed a multi-scale approach, using population abundance data of 170 common bird species from 2004 to 2023 across continental Portugal. In addition to a national-scale analysis, sub-national approaches were conducted, where bird census cells were clustered into categories (low, medium, high) based on their 2020 HFI or GDP values. By stratifying the territory in this way, we aimed to capture the trends and relationships between the variables in different socio-economic contexts – one reflecting the degree of landscape transformation and the other the economic scale. At each scale, multi-species indices for common, agricultural, and forest birds were first calculated, and then used as dependent variables in time-series models with either the HFI or the GDP as independent variables.

Insights

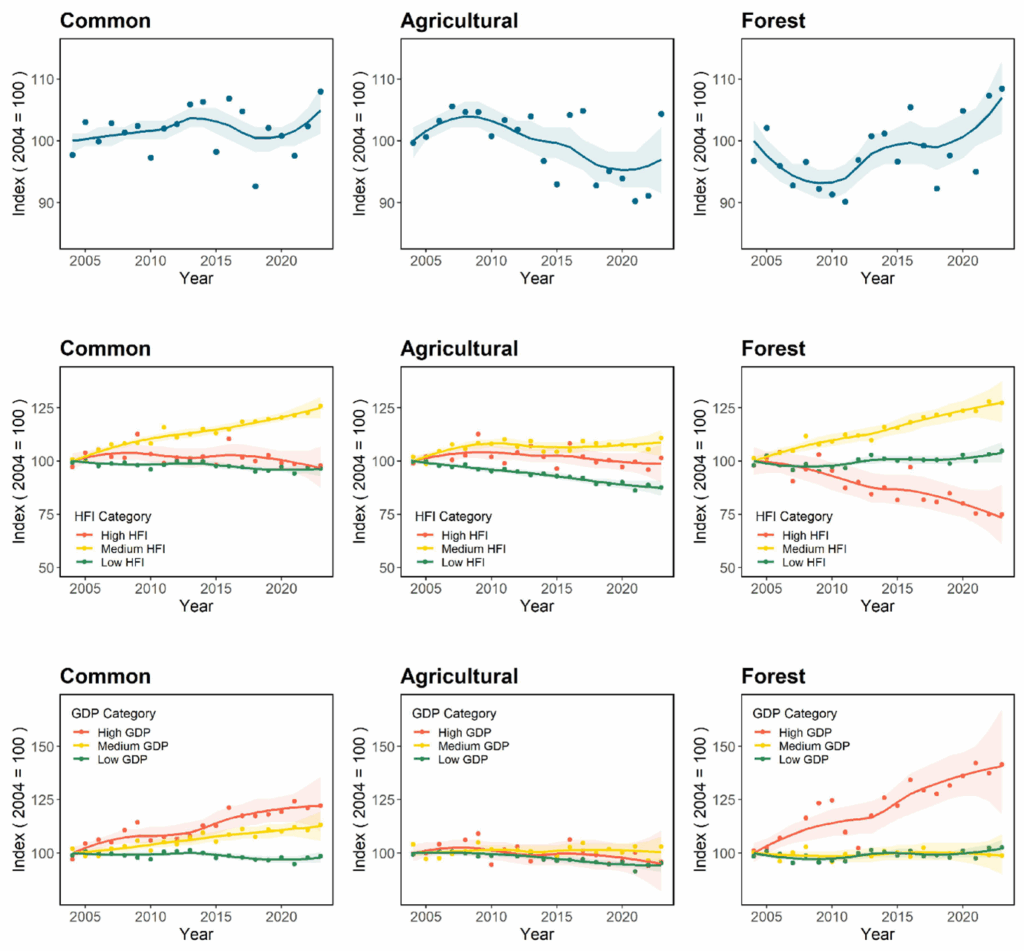

The national trends align with those reported for Europe, where populations of agricultural birds generally decline, and forest birds show stable or increasing populations (image below). In contrast, sub-national patterns highlight the context-specific nature of population trends and reinforce the value of conducting assessments at finer spatial scales.

When looking at how bird populations have changed over time in relation to the two explanatory variables, models based on HFI stratification and using HFI as a predictor showed more and stronger long-run relationships at sub-national scales. This suggests HFI’s suitability as a direct predictor as it captures direct pressures on ecosystems, such as urbanisation. In contrast, GDP was a weaker predictor, reflecting its indirect and less consistent relationship with biodiversity. More long-run relationships were found for agricultural birds, which responded to HFI across both HFI and GDP clusters. Forest birds, however, only responded to HFI within HFI clusters.

Within the significant models, the findings pointed to a negative effect of human activity and land use on bird populations over time. Such outcomes align with the usual expected conflict between direct human pressures and biodiversity conservation. However, there were a few exceptions, namely forest birds in medium and low human pressure zones. In these cases, increasing population trends were observed, suggesting that these species may be recovering in those areas due to specific changes in ecosystem use and management – despite rising human pressures – indicating that, in some contexts, increasing human presence can be compatible with biodiversity recovery.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the study emphasises the complex relationship between biodiversity change and human pressures, showing that direct impacts have a stronger and more consistent influence on biodiversity trends than broader economic indicators. The predominantly negative associations point to ongoing socio-economic pressures on bird populations. However, the magnitude and direction of the impacts vary across spatial scales and socio-economic contexts, underscoring the need for sub-national approaches to inform effective conservation policies.

Read the full article in Sustainability below:

The full article may be cited as:

Baptista, L.; Domingos, T.; Santos, J.; Proença, V., 2025. How Do Bird Population Trends Relate to Human Pressures Compared to Economic Growth?. Sustainability, 17, 3506. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083506