Climate change and increasing economic inequality are two of the most pressing challenges of this century, and they are closely interlinked. Poorer households are more exposed to climate impacts and spend a larger share of their income on energy and essential goods, making them particularly vulnerable to price fluctuations and thus to climate policies if they are not designed with social equity in mind. At the same time, high-income households account for a disproportionate share of carbon emissions through their consumption patterns and investment choices. This creates a central policy dilemma: redistributive policies that aim at reducing inequality may stimulate consumption and economic activity, potentially increasing carbon emissions, while climate policies may exacerbate inequality if their distributional effects are not carefully managed.

In a recent paper published open access in the Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, we address this dilemma by testing which fiscal policy packages can simultaneously reduce economic inequality and carbon emissions while improving macroeconomic indicators such as employment and financial stability. To tackle this question, we move beyond standard equilibrium-based climate-economy models and use an agent-based integrated assessment model calibrated to the European Union. Agent-based models are better suited to capturing distributional dynamics, financial instability and non-linear feedback effect respect to mainstream models; this modelling approach allows to represent heterogeneous households, firms and banks, and to study how their behaviour and interactions influence the economy.

Why single policies fall short

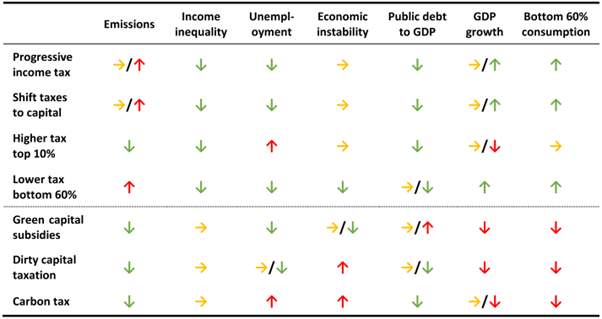

We test two broad groups of fiscal policies. The first consists of progressive fiscal policies, including more progressive labour income taxation, shifting taxation from labour to capital income, higher taxes for top-income households, and lower taxes for bottom-income households. The second consists of green industrial policies implemented through fiscal policies as well, such as subsidies for low-carbon investment, taxes on more carbon-intensive capital, and carbon pricing. We first assess these policies in isolation and then explore a wide range of policy combinations.

A first key result is that no single policy instrument can achieve both lower inequality and lower carbon emissions on its own without significant drawbacks. Progressive fiscal policies reduce inequality and thus support aggregate demand, as lower-income households tend to consume a larger share of their income. This improves employment and economic stability. However, higher demand for goods and energy can lead to higher emissions, when production remains equally carbon intensive.

Green industrial policies show the opposite effect. Policies that incentivise cleaner investment or put a price on emissions reduce emissions by steering firms away from carbon-intensive technologies and reducing energy use. Yet, when implemented in isolation, they may slow economic growth, increase financial instability, or disproportionately affect lower-income households through higher energy costs.

Combining policies to achieve multiple goals

Because individual instruments pull in different directions, the central question becomes whether policy mixes can achieve multiple goals at once. We therefore run a large scenario exploration across many combinations and intensities of these policies. Our core finding is that well-designed policy packages can reduce both inequality and emissions while improving economic outcomes. In particular, the most successful policy packages combine:

- progressive fiscal measures that support lower-income households;

- green industrial policies that lower the carbon intensity of production, such as subsidies for cleaner capital;

- a relatively mild carbon tax that helps finance the other policies.

Importantly, the study finds that these positive outcomes depend on policy coordination. Redistribution strengthens economic stability and employment, while green subsidies and carbon pricing steer production and investment towards cleaner technologies, offsetting the emissions increase that redistribution alone would generate.

Growth and carbon emissions

Another important finding concerns the relationship between economic growth and emissions reduction. Our results show that increasing economic growth and decreasing emissions can be achieved simultaneously to a certain extent, beyond which a trade-off emerges: aiming for greater emissions reductions limits the potential for boosting GDP growth, while prioritising economic growth reduces the achievable emissions reduction.This highlights a fundamental policy tension: the issue is not whether increasing growth and reducing emissions are compatible in absolute terms, but whether economic growth is compatible with increasingly stringent climate targets.

Overall, the study provides clear evidence that reducing inequality and emissions is possible, but not automatic. Approaches that rely on single instruments or treat social and environmental goals separately are unlikely to succeed. Instead, success relies on the careful co-design of redistributive, environmental, and industrial policies, through methods that properly capture ecological boundaries, economic dynamics and technological change.

Read the full article in the Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization below:

The full article may be cited as:

Ravaioli, G., Lamperti, F., Roventini, A., & Domingos, T. (2025). Tackling emissions and inequality: Policy insights from an agent-based model. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 273, 107188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2025.107188